From drought to floods to finding a means of crossing cattle

to market, water has been a constant theme throughout Texas history.

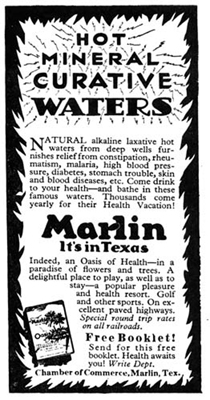

But there once was a time when Texas’ natural mineral water

was touted as a cure for everything from rheumatism to polio.

Across the Brazos River Basin, an entire health care industry sprang

up around the artesian waters; with thousands of visitors flocking to the springs seeking the water’s supposedly curative qualities.

With the mineral water craze, communities experienced booms and busts.

Waco, site of the Brazos River Authority’s central office, owes its birth and

early growth to artesian water. Beginning in the mid-1800s, the city was built on the site of an Indian village located around a spring

near the Brazos.

Later that century a Waco resident tapped into ground water and created the city’s

first hot-spring, artesian well. Soon other wells were drilled and the mineral-rich water that pushed up from the Trinity Aquifer was left

to flow from what residents then considered an endless supply, said Dr. Joe Yelderman with Baylor University’s Geology Department.

“Getting that groundwater was an advantage for people in Waco,” Yelderman said.

“There was plenty of it and it was easier to treat than the river water.”

Soon those flowing wells earned Waco the nickname, “Geyser City.” For the next

several decades, well water played a vital role in the city’s growth, supplying most residents with drinking water until Lake Waco was built,

Yelderman said. Water from one such well in the city was used to make a fledgling soft drink brand, Dr Pepper. Another well supplied water to

each of the 22 floors of Waco’s Alico building, the tallest building west of the Mississippi for the early years of the 20th century.

Mineral baths, spas and pools, known as natatoriums, sprang up in Waco, Marlin, Mineral Wells

and other locations as people turned to mineral water for health care. “Taking the waters,” as the practice was known, was billed as a way to cure everything

from constipation to rheumatism to arthritis, according to the Handbook of Texas Online. Decades before a polio vaccine was developed, clinics were set up to

use mineral water to treat the crippling illness.

“People talked about the water like it was a magic potion,” Yelderman said.

“They had all kinds of claims about its benefits. Later on, that died down when people realized that wasn’t the case.”

A medical industry grew around the wells and the populations exploded in some cities in the

Brazos River basin. Marlin, southeast of Waco in Falls County, drew about 80,000 visitors annually during its peak in the 1930s. In addition to several

spas and clinics, the town featured the eighth hotel by Conrad Hilton and hosted training camps for professional baseball teams.

Mineral Wells, then with a population of 8,000, at one point drew 150,000 visitors a year.

Many celebrities stayed at the city’s showpiece resort, the Baker Hotel, including Will Rogers, Judy Garland, Clark Gable, Tom Mix and even the

Three Stooges, according to the Texas Almanac.

In many cases, the fortunes of a town rose and fell with the popularity of the

local mineral baths. An extreme example was Wootan Wells, about 10 miles southeast of Marlin.

By 1890, the community's mineral water drew 2,000 visitors a year. But within a few

decades, the rise in popularity of the nearby Marlin resort and a series of devastating fires and floods wiped out Wootan Wells. Today,

the only clue the community existed is a historical marker near State Highway 6 in Robertson County.

The advent of antibiotics and medical advances spelled the end of the mineral water resorts.

Today in Mineral Wells, a group of businessmen are attempting to restore the 14-story Baker Hotel to the opulence of its heyday, though one can still

buy “Crazy Water,” bottled in the city.

In Marlin, the spas and bathhouses have been demolished. Nearby, though, a public fountain still

spouts a constant stream of warm mineral water from deep beneath the earth.

Today, few give credence to claims of mineral water’s curative powers, though groundwater continues to play an important

role in supplying the needs of people in the basin.

According to the State Water Plan, the statewide amount of groundwater available to use is expected to

drop by 22 percent over the next 50 years to about 5.8 million acre-feet per year. Thus, conservation of both ground and surface water will be essential to

meet future needs.

Bouncing back from a shortage takes much longer for groundwater because it has to filter down

through the earth to the aquifer, said Brazos River Authority Hydrologist Brad Brunett.

“The beauty of surface water is that is it can be quickly replenished. One big flood event can

fill up a lake and provide a stored water supply that can last multiple years,” Brunett said. “That’s not necessarily the case with groundwater.”